Why you are spending too much time on the wrong thing

Tolstoy once said, “All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. Not sure whether a notoriously bad husband should be consulted on the subject of familial relations, or whether a novel where the main character meets her end on the train tracks is a good place to look for life advice in general, but one thing is certain - there are plenty of ways aimed at getting things done that lead to nowhere. Visualisation. Product roadmaps. New Year resolutions. OKRs and KPIs.

This is not to say that various goal- and metric-setting methods are useless. Clearly it can only help to know where you are trying to get when you are going somewhere! However, this in itself is not sufficient. Actually getting stuff done requires one crucial ingredient - a process.

Speaking of getting things done, here are a couple of books that I enjoyed recently: Inspired: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love* by Marty Cagan (modern product manager’s Bible) and Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones by James Clear (a self-help bestseller with a self-explanatory title). Despite having been written on different subjects, both of these place emphasis on the importance of the right processes being put in place in order to achieve a goal. The idea must pre-date the invention of the printing press, but judging from the sheer amount of time and resources that both companies and individuals spend on setting goals instead of changing their practices, this is one of those truths that many of us can benefit from revisiting.

Winners and losers have the same goals.

James Clear

If setting a goal was what differentiated those who do from those who do not, gym attendance would not fall quite so sharply after the month of January (or September, for those of us based in France - my soon-to-be compatriots are all about the post-summer rentrée). As James Clear puts it, “Every Olympian wants to win a gold medal. Every candidate wants to get the job. And if successful and unsuccessful people share the same goals, then the goal cannot be what differentiates the winners from the losers.” ‘nuff said.

Again, this is not to say that goals are pointless. One might say that they are required but not sufficient for a positive outcome: identify a goal to set the direction for your efforts, but don’t dwell on it past that point. You know the Pareto principle? 80% of the outcome is driven by 20% of the input? Goals are not these sought-after 20%, so stop spending 80% of your time on them.

Typical roadmaps are the root cause of most waste and failed efforts in product organizations.

Marty Cagan

If you don’t work at a tech company, you might not know what a product roadmap looks like. In a nutshell, a roadmap is a list of product releases/features projected to come out at certain points over the course of some time period (say, a year). Basically, these are goals with strings attached. Obviously, release planning is necessary for any company to stay afloat: the management needs to have some idea about what comes out when in order to plan ahead, as well as address any inter-departmental and team dependencies. According to Marty, however, there are two reasons for why most product roadmaps fail to deliver:

“At least half of our product ideas are just not going to work.” There are simply too many unknowns for a product manager to be able to sit down and come up with a list of features guaranteed to be valuable to the user, feasible for the engineers, and viable in the company’s business context.

“Even with the ideas that [hit all the right points], it typically takes several iterations to get the execution of this idea to the point where it delivers the expected business value.” Treat your roadmap as a constant work in progress. Make maintaining and updating the roadmap a part of your process, rather than the goal that you set once and for all.

Lesson # 1: goals are overrated.

Set them quickly, do not get too attached, and be prepared to iterate. Let the goal be the input to feed into your process instead of the (pardon the pun) end-goal in itself.

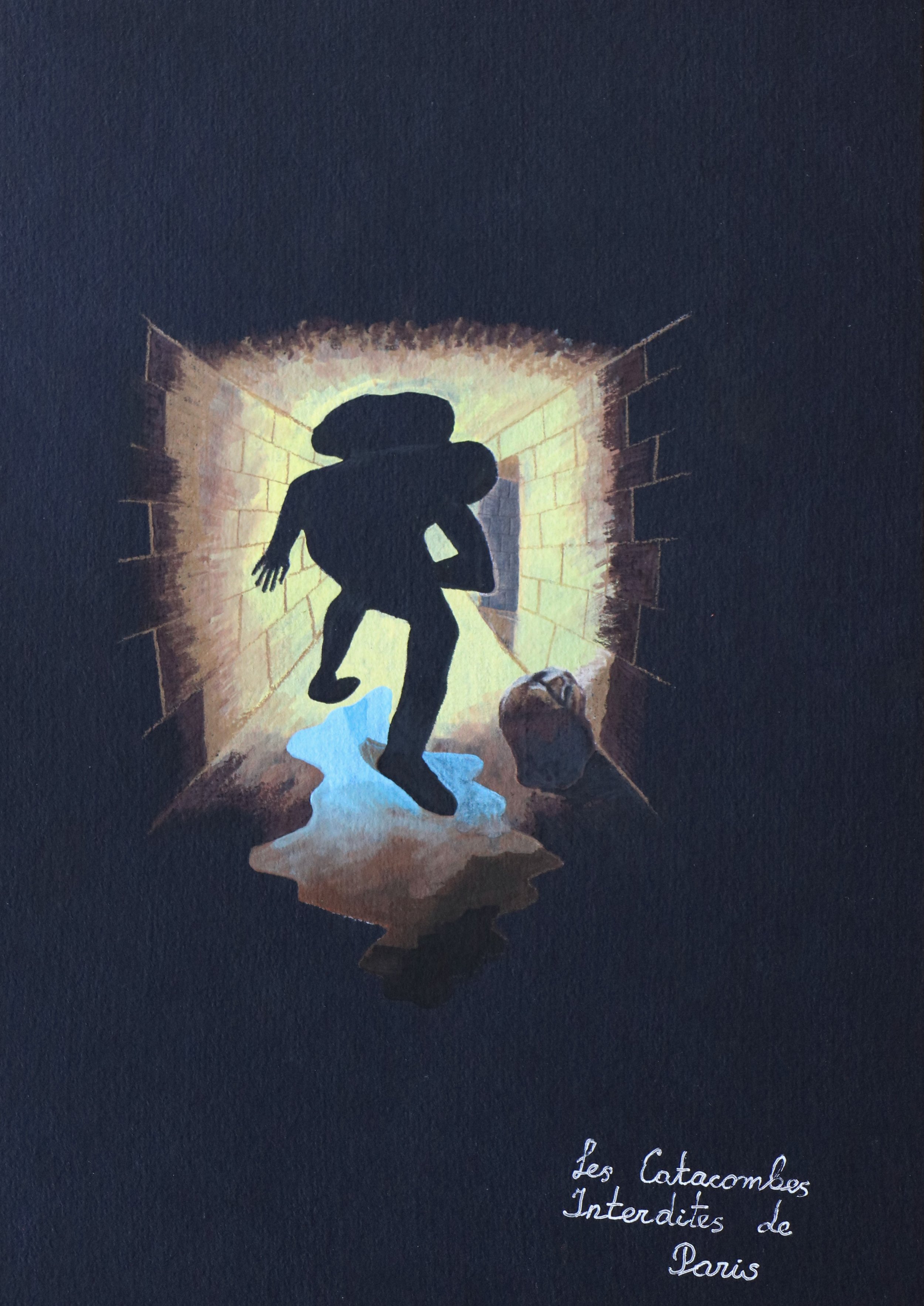

You know what isn’t overrated though? Original art. Check out the paintings in my Art Shop below:

Continue reading ↓

The goal is not to read a book, the goal is to become a reader.

James Clear

I know, I know, for someone who said that goals are overrated I sure am spending a lot of time on them. However, this is a key idea that applies to both habit formation and product management.

When setting a goal, make it about your identity, rather than an individual action / one-time accomplishment. The goal is not to lose 10 pounds, the goal is to become healthier. The goal is not to pass a French language test, the goal to become a French speaker. Reframing a goal in this manner makes it much easier to go from the goal to the process that will shape you into the person you want to become. What does a French speaker do? Speak French, duh. Incorporate the language into as much of your daily life as you can, and you’ll be well on your way to accomplishing the task.

It is all about outcome rather than output. … Each item [on the roadmap] is stated as a business problem to solve rather than the feature or project that may or may not solve it. These are called outcome-based roadmaps.

Marty Cagan

One of the purposes of having a roadmap is that it [supposedly] helps to make sure that the items with the highest business value get prioritized. Supposedly. Because once added to the roadmap, the items (features, or products) stay on it long after the business value discussions are forgotten. Did I mention that half of these product ideas will fail to deliver the intended business value in the end? Not even because the product team was not good enough - the high failure rate is simply a consequence of the world being a dynamic system with far too many unknowns to tackle.

Instead of packing the roadmap with features paired with to-be-delivered-by dates, Marty’s solution is to basically replace the whole thing with OKRs. That is, Objectives and Key Results, where the latter are some sort of metric measuring your success (or lack thereof) in achieving the objective.

One of the OKR examples used in Inspired was: objective - “Dramatically reduce the time it takes for a new customer to go live” with a key result - “Average new customer onboarding time less than three hours”. There are many different ways that a product can accomplish this goal (not to mention, many more for it to fail spectacularly). The basic idea is: give your product team the business context that it needs, tell them what outcome you want, and let them decide how to deliver it.

Lesson # 2: when setting a goal, focus on what you actually want to accomplish instead of narrowing it down to a specific solution right away.

Don’t say you want to lose 10 pounds if your actual goal is to get fit. Losing 20 pounds of muscle mass and gaining 10 pounds of fat aligns with your “minus 10 pounds” objective, but that isn’t what you want, is it? Same thing applies to the workplace: why put “deliver a new sign-up flow” on your roadmap when what you are actually after is getting XX new customers for your product? Identify the business objective, and let the team figure out the correct path to success.

When you're in motion, you're planning and strategizing and learning. Those are all good things, but they don't produce a result. Action, on the other hand, is the type of behavior that will deliver an outcome.

James Clear

I have a confession to make: I love planning. I don’t mean making grocery lists or organizing events; I love planning out and around the activities I enjoy. Planning is basically a hobby in and out of itself! In my former physicist life, I always had on me a Moleskine to note down possible research projects to ponder later on. Upon leaving academia to become an AI engineer, I replaced it with a sleek Castelli notebook where I kept ideas for blog posts and R&D work in machine learning. During my subsequent transition to product management I filled pages of a Paperblanks journal with product ideas and market research. (As you may have noticed, I am a hopeless stationery junkie. I don’t know which came first - the planning or the stationery, but the two feed into each other like two conspiracy theorists over a Sunday brunch.)

Lots of good things came out of my planning and learning (which James collectively refers to as “motion” to set it apart from “action”). I never run out of ideas because no matter how blank my mind can be at any particular moment, I know that all I have to do is open my notes and pick whatever strikes my fancy out of a list. However, if I am being honest, planning is also my biggest source of procrastination. A sneaky one, too, because it is easy to feel productive (i.e. “in motion”) when you are brainstorming ideas or doing research for a project. The truth is, these activities are only productive if you end up taking action and actually producing something in the end. Otherwise, they are merely a form of day dreaming - not that there's anything wrong with that, as long as you take it for what it is.

Discovery and delivery are our two main activities on a cross-functional product team, and they are both typically ongoing and in parallel.

Marty Cagan

Product discovery is exactly what the name suggests: various activities aimed at discovering what product should be built in order to satisfy the business objectives. This is a major part of the product manager’s job, and it is what takes you from the idea to product-market fit. Actually, in reality the trajectory might be more like: idea to another idea to prototype back to idea to another prototype to product, repeated multiple times until reaching the elusive product-market fit. But you get the point.

There is product discovery, and then there is product delivery. Delivery is also an iterative process, at least when it comes to software: in modern organizations, the software that they deliver to customers may be updated on a weekly, or even daily basis.

Now, there are two ways of going about discovery+delivery: one is known as waterfall and the other agile. In the waterfall world, you would sit down and discover to your heart’s content. You would interview users, survey the market, map user stories, build prototypes - everything short of actually building a working product. In the agile universe, you would do a bit of all those things, and build a product. This first version would likely be crappy, but at least you will find out why and how it can be improved. With that newly-found knowledge, you would go back to product discovery, and then quickly put the next version together. This way you would be far less likely to spend months in development only to deliver a product that works, but ultimately fails to achieve your business objectives (the sad reality of many a waterfall organization).

Lesson # 3: have a bias for action. Do the prep work, but start actually doing stuff as soon as you can.

You can always go back to the research stage at any time - and with better insights than you would have otherwise.

When you want to increase your productivity, acquire a new habit, or undertake a new challenge, whether on a personal or company level, it is tempting to set a SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time bound) goal or five, brainstorm what KPIs go with your OKRs, and fix some delivery dates on a pretty roadmap. The truth is that if these are the only changes you introduce into your life, there is little reason to expect any effect on your outcomes. If last year’s resolutions failed to stick, why would this year’s? If your organization has not been able to innovate, would two days or release planning for the upcoming quarter really make a difference?

Goal-setting and planning are only efficient when they are used to drive changes in your processes. I have intentionally avoided talking about the latter in this blog post - mainly because that’s the point where best practices for individuals vs. organizations diverge, whereas here I wanted to focus on the similarities. I will follow up with more blog posts on the topic in the future, but in the meantime I truly cannot recommend Inspired and Atomic Habits enough!

* This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which the author may earn a commission from for qualifying purchases.